For decades now, conservative lawyers have hunted for suitably sympathetic plaintiffs to bring anti-affirmative action cases to the Supreme Court. The latest precedent targeted for overturning by (the presently right-wing, activist) SCOTUS is Grutter v. Bollinger, a 2003 case whose primary holding is:

The use of an applicant's race as one factor in an admissions policy of a public educational institution does not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment if the policy is narrowly tailored to the compelling interest of promoting a diverse student body, and if it uses a holistic process to evaluate each applicant, as opposed to a quota system

Source: Justia

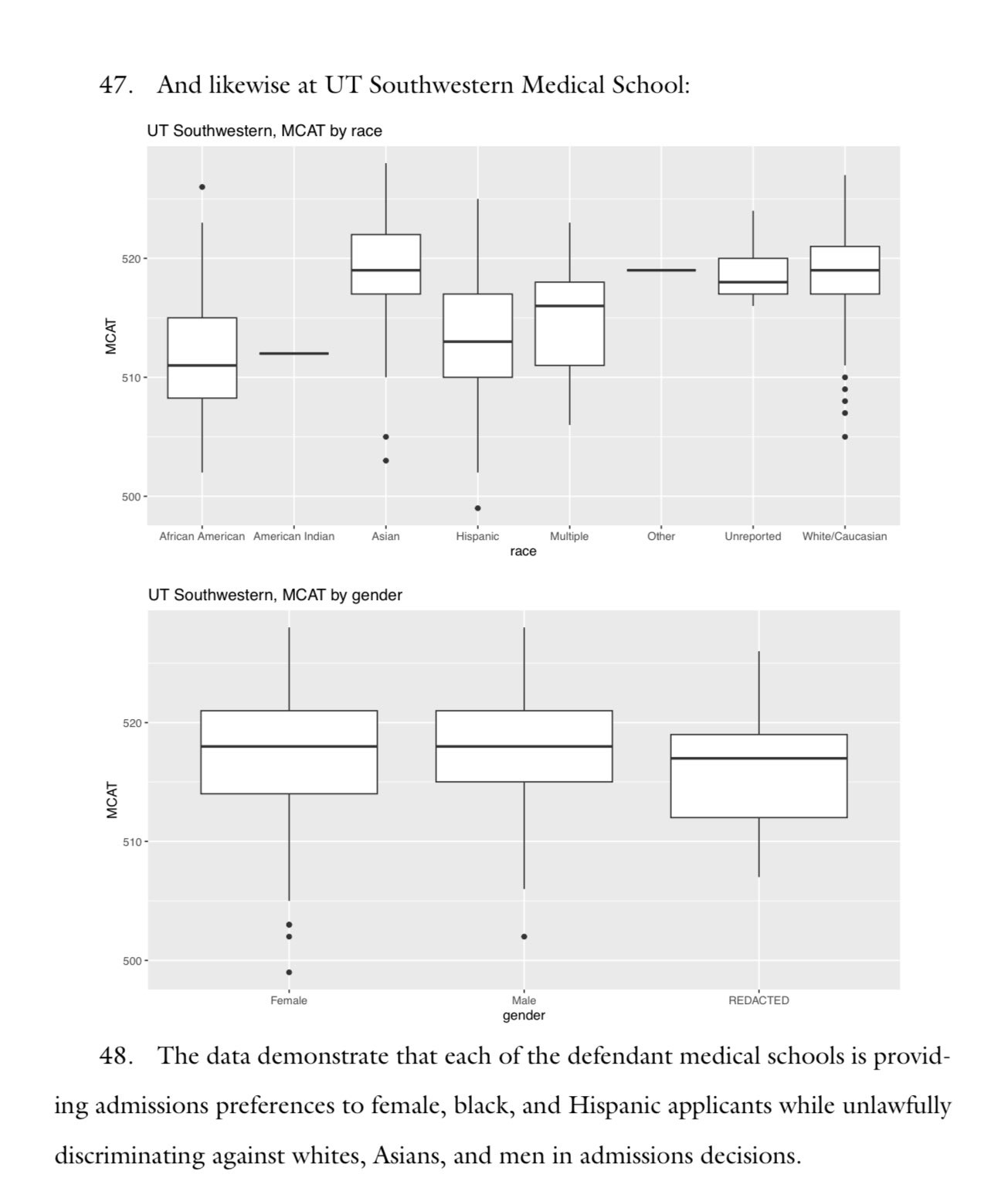

Curiously enough, the plaintiff in this latest case is a medical school applicant suing six Texas medical schools for practicing “discriminatory” admissions policies. In particular, after filing for an open records request for the medical schools admissions statistics, the white male student claims he was rejected in the place of Black, Hispanic, and female students with “inferior” academic credentials. It’s not worth expending any cognitive effort taking conservative crusades on their face or in any kind of good faith, but I think this particular case is exemplary of a deeper rot in our cultural attitudes towards higher and particularly professional education.

While most people in academic medicine might roll their eyes at this lawsuit, or, if they’re motivated enough, reiterate the value of diversity in medicine, I can’t shake the pernicious feeling that the core ideas which fuel the conservative crusade against affirmative action are still the mainstream and unquestioned dogma of academia and if I were to anonymously poll the whole of medicine on the question “Do you believe that medical school admissions should be a meritocracy?” most people would answer in the affirmative. Let me explain why this is wrong.

The Banality (and Myth) of Meritocracy

To believe in the possibility of meritocracy you must believe in three things:

There are objective criteria by which merit can be measured

We know what these criteria are and are able to measure them

These criteria are not influenced by externalities outside of an individual’s control

In medical school admissions, the examples given for so-called “objective” criteria are an applicant’s GPA and MCAT score. Indeed, this is the basis of the aforementioned lawsuit: the plaintiff got a hold of a spreadsheet of GPAs and MCAT scores, saw the average for minority and female students was lower than it was for white and Asian men and concluded that there was no explanation other than the illegal application of race as a criteria in admissions (challenging the holding in Grutter v. Bollinger which clearly states that this is, even if true, is not, in fact, illegal). But we all know that GPA can be gamed and varies drastically by academic major, institution, or even by different sections of the same course simply because they are taught by different professors, and as for the MCAT and standardized tests like it, well, I think Dr. J.B. Carmody put it well in his blog post about merit in medical education:

In a highly-competitive processes like medical school admissions or residency selection, students will push themselves to the limits to distinguish themselves by whatever metric is used to determine the winners. But here, too, privilege is important. To engage in the hard work involved in standardized test preparation requires having the luxury to do so. And when the competition is intense and all the competitors’ engines are turning at their maximum rpm, the small degrees that separate winners from losers often have more to do with different starting points than different top speeds.

I think it can be hard for people who aren’t in medicine to understand what people mean when they criticize supposedly standardized exams like the MCAT or the USMLE Steps. Isn’t standardization good? Don’t we all want to be certain that the people training to take care of us are well-equipped to do so? Sure, but the level of performance on standardized exams at which selection happens (i.e. where people are actually competing for seats) is far higher than the level at which maximal utility of the exam is achieved. Let’s take a look at the graph submitted by the Texas lawsuit plaintiff which is meant to show us how medical schools illegally discriminate against white and Asian men.

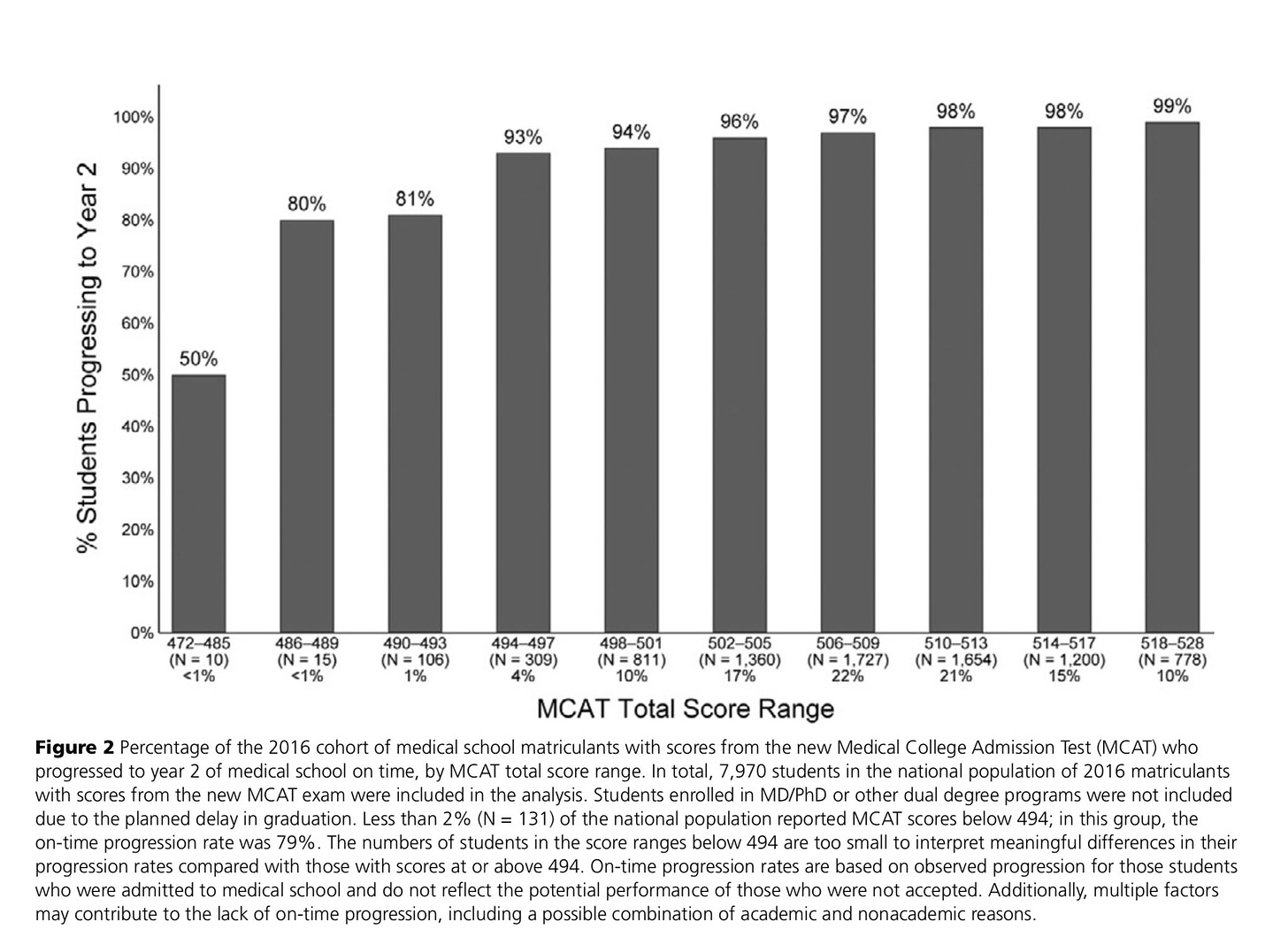

Now let’s take a look at a graph of the MCAT’s main academic predictor: the ability to progress through the medical school preclinical curriculum in a timely fashion.

The plateau for the MCAT’s ability to predict timely progress begins at the 494-497 score range, well below the vast majority of all admitted students represented in the plaintiff’s boxplots, regardless of race or ethnicity. So, even if you flatten out “merit” to the single, narrow, and arguably almost meaningless dimension of “success in the preclinical medical school curriculum”, there is nothing “less meritorious” about someone scoring a 504 compared to someone with a 528.

But let’s not focus for too long on the easiest case to knock down. What should the criteria for meritocratic admission to medical school be? Posed another way, what qualities do we want our future physicians to have? I had the opportunity to train as an interviewer for my own medical school alongside many members of the local community who were themselves undergoing the same training. As a preliminary exercise, our Dean of Admissions asked our community members precisely this question. The most common and immediate answer was: compassion. Kindness. Understanding. Patience. Professionalism. Competence was there, too, yes, but not genius not brilliance. When people are sick they want someone who cares about, listens to, and suffers with them; someone who is invested in seeing them get better not just as an academic exercise of their command over their field but as a fellow human being. I thought it was heartwarming, but also darkly funny. Can you imagine what they would think if they saw what medical school was actually like?

Those qualities which might be the real meritful criteria of medical school admissions are invariably difficult to measure, and by no means objective. Someone who volunteers their time helping the less fortunate might be compassionate, yes, but if everyone knows that you need to volunteer to get into medical school then what does that mean? And if we have seven thousand applications in front of us and can only interview three hundred for ninety slots at our medical school, how do we decide who is the “most compassionate”? The quantity of their volunteering hours? The quality of recommendations from people who volunteered with them? It’s a typical problem and in general any quality which can be easily measured is not likely to tell you much about deeper but more meaningful qualities like compassion, and any quality which is difficult to measure will rarely be objectively interpretable. If you are one of those people who believes in the possibility of meritocracy, knowing this can you go back to the three criteria I provided and still defend the idea?

In truth, the problem our medical school admissions process is trying to solve is not that there are only a rare crop of meritful students in the pool of fifty-thousand or so students that apply to medical school every year, it is that there is an artificial scarcity of higher educational resources. I wrote at some length about this in my post about racism and racist ideas in science. In short, the idea of merit on its own is not benign and the deeply connected mythologies of merit and genius in academia are rooted in eugenics and racism that ultimately perpetuate exclusionary and intellectually toxic environments for the whole field and likely stifle innovation, progress. Quoting myself here:

Genius, like meritocracy, is another myth and one familiar, in particular, to social and natural scientists alike. When researchers asked other researchers across a variety of fields how important innate ability, genius, or brilliance were to success in their field, the results showed a clear trend where fields in which innate ability was most valued were far less female, and less Black (Leslie, Cimpian, Meyers and Freehand *Science* 2015]).

The racist stereotype which primes individuals to assume the intellectual inferiority of some kinds of people and not others is, at the very least, correlated with the ability of a field to recruit, retain, or support those individuals. As with medical schools and meritocracy, it is not innate ability or brilliance which is being measured and then applied during selection to "ensure the health" of the field, but a collection of racialized biases which are then confused for brilliance. Nevertheless, an impression or gestalt of genius built on top of racist structures is used to take the measure of individuals in the academy, and, as Leslie showed, in some fields more strongly than others. The eugenicists, of course, were similarly enthusiastic for "enriching the stock" of their field as they were for all of humanity. "A profession must have power to select its own members, rigorously to exclude all inferior types" writes Ronald Fisher (of Fisher's exact test fame, and eugenicist infamy) in the Eugenics Review (1917).

What is diversity in medical education for?

Most people’s intuition of “affirmative action” like policies is that they exist to correct a historic injustice: Black and brown people were and are being excluded from higher education, and we must work to correct that. But in medicine there is another element at play, namely that it really does matter who is in the room, and I’m not just talking about the patient. There have been many kinds of studies done on the effects of racial concordance or dissonance on this or that measure of healthcare delivery or quality of care––for example, one study found the racial gap in mortality between Black and white newborns (where Black children face higher mortality rates) is halved when cared for by Black physicians––but that’s not actually what I’m referring to. I believe that much of the progress we have made in rolling back racist ideas and structures in medicine––and we have a very long way to go––has been made precisely because the diversity of the house of medicine has grown. Same goes for progress made in sexual and reproductive health, where there is also still much work to be done, particularly with respect to LGBTQ+ patients. The fact is that medicine has been greatly enriched and advanced in leaps and bounds in a very short period of time by the modest gains that have been made in the diversity of the profession. As much as we like to make fun of inane, wet-noodle corporate DEI policies in the medical ivory tower (like “challenging” your male employees to generously donate thirty minutes out of their week to “engaging women in meaningful conversation”), diversity has very real, lasting, positive impacts on our profession. It is not simply a means to making white people less racist, or merely reparations for historical injustice, it is a critical piece of the shovel that we use to dig out of the intellectual dark ages of racism, eugenics and barbarism which are the extremely recent (present) legacy of our profession.

I don’t think any of these ideas are particularly novel or revolutionary, actually the medical community in the U.S. has been having some version of this debate for nearly 200 years. That link leads an excellent JAMA article (2008) on the history of racial segregation in medical education and training in the United States. The summary is worth repeating here:

In the United States, organized medicine emerged from a society deeply divided over slavery, but largely accepting of systemic racial inequities and theories espousing black inferiority. Emblematic of existing societal values and practices within the profession, medical schools, residency programs, hospital staffs, and professional societies largely excluded African Americans. For more than 100 years, many medical associations, including the AMA, actively reinforced or passively accepted this exclusion. Still, throughout this history, vocal groups of physicians—black and white, and within and outside these associations— challenged segregation and racism…

…With the civil rights era, US medicine, like the nation, entered a period of profound change. Most recently, AMA support for this independent exploration of its history is, itself, a part of an ongoing professional evolution. Yet despite much progress, this legacy continues to adversely affect African Americans. African Americans in 2006 represented 12.3% of the US popula tion, but just 2.2% of physicians and medical students. This is less than the proportion in 1910 (2.5%), when the Flexner Report was released. The care of African Americans remains largely segregated, which contributes powerfully to racial disparities in care. And, not surprisingly given this history, African Americans remain underrepresented in the AMA.

In the earliest days following the termination of slavery, the argument made by the AMA for the exclusion of Black people form medical education was explicitly that “the Negro brain is nine cubic inches less than the Teutonic [European].” Today, there are fewer faculty claiming to know the size of someone’s brain by the color of their skin walking around the medical ivory tower, but there is no shortage of esteemed members of our faculty who quietly or loudly believe that standardized exams are accurate, meaningful representations of generalized intelligence. Some former deans of the nation’s most elite medical schools (Harvard and Penn) even make regularly scheduled appearances in places like the Wall Street Journal to scold the entirety of medical education for “going woke” or foregoing real subjects like the basic sciences for courses on the social determinants of health (nevermind that social determinants are several thousand times more relevant and impactful to global human health and a virtually nonexistent part of medical curricula or examined material). The social sciences in general are highly undervalued, underfunded by the nation’s medical schools and it is not an area schools seriously attempt to compete with one another on (unlike, say, basic scientific research).

In spite of centuries of completely ludicrous debate about completely fake ideas like “intelligence” or “merit”, and so on, we are still here, in 2023, watching a white man with a petty grievance and an outlandish sense of entitlement be bankrolled and coddled by activist right-wing lawyers, in all probability to the Supreme Court of the United States, and in all probability winning the case in their favor. They probably won’t even go to medical school, in the end, but the medical education of the nation will be impoverished anyway, as a result. What frustrates me the most, as someone who is underrepresented in medicine is not that some people just assume I’m dumber than them. It is not even that a lot of those same people who think we somehow took a shortcut to medical school admissions are our superiors and seniors in the medical hierarchy. What bothers me the most is that we have zero expectations of those people to ever change or even learn something new about the sociological or political underpinnings of health, medicine, and human biology, and then are more than happy to pretend that medicine is supposed to be “meritocratic”, even as an ideal.